Did it Work? Matty Healy’s Experiment and the Problem With Live Performance.

“It’s not that I’m fond of dropping Easter Eggs, it’s just that I find that the best art — and I do make art, thank you very much — the best art makes you feel personally addressed. It makes you think, ‘they’re talking to me’. I want to reference that I know that you know that I know.” — Matty Healy

Live In Concert

Walking into Fiddler’s Green Amphitheater, I feel a bit like a sore thumb. Wearing sensible sneakers and not a warm enough jacket, I am uncool and aged amongst the sea of identical leather jackets, white button-ups, and Doc Martens.

It had been eight years since I saw the 1975 live. I’ve flown across the country to see this show with my best friend, bravely buying tickets for General Admission, and hoping and praying I won’t need to pee during the set.

It’s a perfect night. A solid, spectacular show and a generous crowd.

Everything on this night looks right, sounds right, feels right as the head rush lingers from jumping and screaming in revelry.

Yet something feels off — unsatiated, unfulfilled — like an expectation unmet. It’s almost like I was missing something.

It hits me. I was missing the POV.

Many of the concert clips I was fed on TikTok (and Instagram and Twitter), presented the experience from a personal point of view, capturing Healy or other members of the band either framed oh-so-perfectly in the shot or starting directly into the camera.

However, when immersed in the live performance, it became evident that a concert is, first and foremost, a performance. It’s not as if this is my first concert experience, but something about a 1975 show on this tour is different.

The Box is a Screen

For a band like the 1975, it’s easy to clock their fans online with the Box in their Twitter handles or tattooed on their bodies. The band’s insignia — known as “The Box” — has been a monolithic presence since the band’s first EP.

In a video with BBC1, the band’s frontman Matty Healy says The Box was picked up from an old Chanel ad.

“We wanted something to look more like a brand than a band.”

Seemingly an innocuous choice as a “chic” logo, over 20 years since Matty Healy, Adam Hann, George Daniel, and Ross MacDonald were joined sonically at the hip, The Box has made a lasting impression on the fans of the 1975.

In September of 2023, the band held a special performance of their Self-Titled album at Reading in celebration of its 10th anniversary.

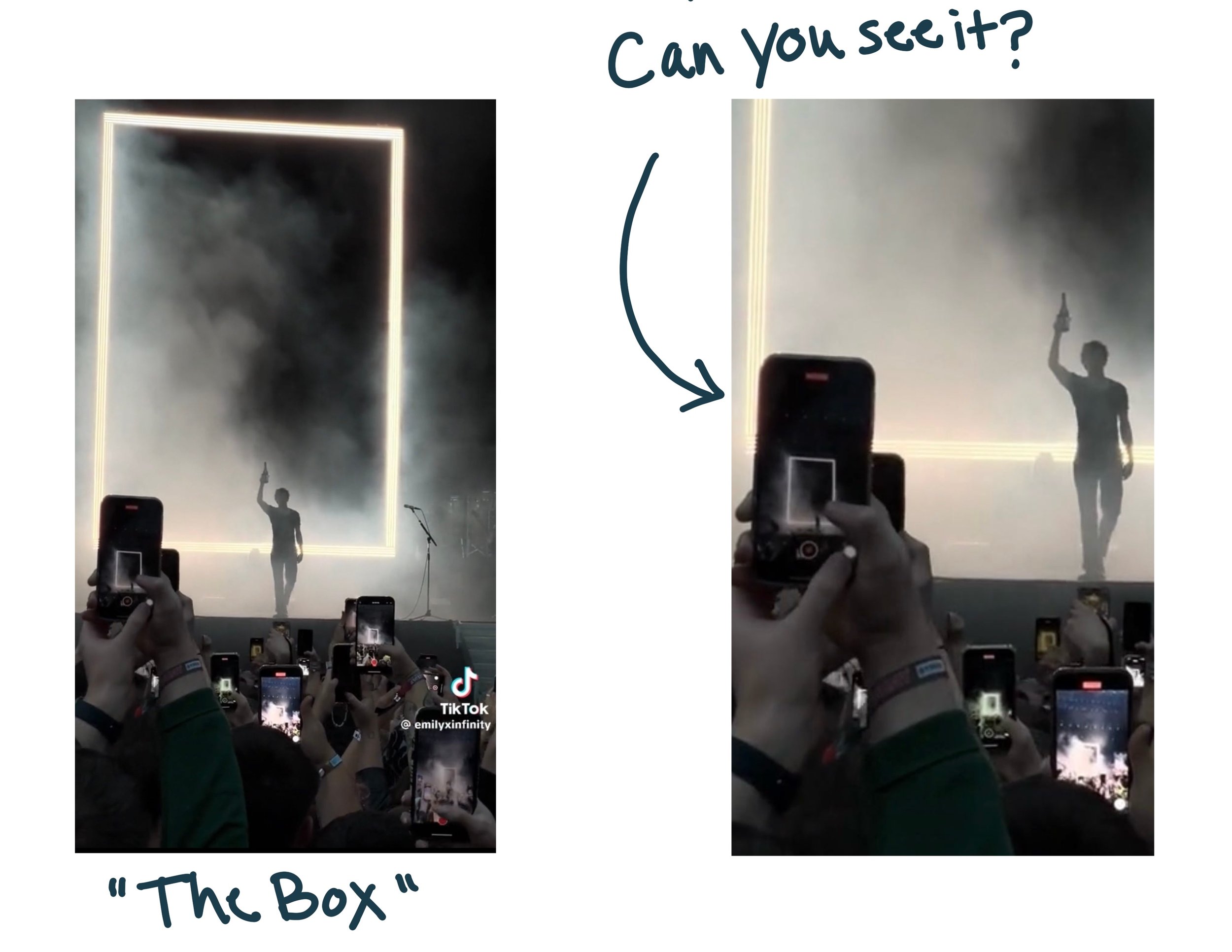

The image of the Box — iconic, idolatrous, glowing, towering over the band, stage, and congregation — framed by an ocean of phone screens captured and documented in vertical orientation is a vision of monumentality.

Screenshot taken from emilyxinfinity on TikTok

Can you see it? Can you see it? Because once you do, it is painfully, stupidly obvious.

The Box is a screen.

The 1975 is far from the first band to have their logo tattooed on fans or worn as a badge of honor, but they are the first to have a symbol with such prophetic significance.

If the Box is a representation of a screen, there are a myriad of implications for its significance in the legend and lore of the 1975.

In the context of cinema, a screen acts as a visual, metaphorical, figurative, and literal threshold. “A threshold always has two sides, as it simultaneously connects and separates. A border can be crossed precisely because a division always implies spatial proximity.” The screen itself is paradoxical as “screens hide and protect, but they also open up and reflect.” (Elsaesser, Thomas., Hagener, Malte. Film Theory: An Introduction Through the Senses. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2015.)

The screen lives on the threshold — a doorway we peer through into the strange narrative landscape of a film. We travel through the void of nothing — the emptiness between our world and theirs, the literal black of the screen at the start and the end of the film — to return transformed.

The hermeneutics of the screen diverges into a great otherness with television, the internet, and social media. Watching a film is a contained experience — you must travel to the theater, walk the hall, and find your seat to be in the company of the screen.

But watching, watching, watching everything and anything on a screen you have in every room — or better yet — right there next to you, where is the context or understanding of what you are watching and why?

The screen here, sitting in the palm of your hand, is turned on its side. It appears to offer a sense of closeness, shortening the proximity between you and everything else. It feels so close, so very nearly real as the feeds personally tailored by the almighty algorithm invite you in.

The context of the screen is altogether abandoned for a manufactured reality. The suspense of disbelief has no home here, as that would require nuance and understanding of your role as an audience to this media.

Dramaturgical Expectations

Headlines are claiming the change in concert culture boils down to fans throwing things at artists on stage or simply as an entitled attachment to unruly, unhinged behavior.

What has been glossed over for the sake of sensationalism is the change in expectations set by social media content. In a post-pandemic, vertical video world, the live concert experience is previewed, pre-judged, and perceived initially through endless out-of-context snippets.

The first leg of the 1975’s tour At Their Very Best included a performance structure of a stage play, but it was shredded of its context on social media, which Healy discussed early on in the tour in interviews.

It is a bit mind-boggling to think Healy didn’t consider the lens of social media would shape the perception of the show, but for Still…At Their Very Best, the second round of the tour, he expected and invited the consumption.

As a fan finally attending their show for the first time in a long while, I found myself expecting to fulfill a role I had envisioned based on the spoon-feeding my FYP gave me — that of the main character.

It just felt differently than I imagined it would, and I didn’t reconcile my rewired brain’s expectations until after the show.

This dissonance between my unrealized and unexpected expectations and the performance of this live show highlights how social media shapes our perceptions of events — often blurring the line between anticipation and authenticity.

But this is not news to me or you.

These recorded intimate moments foster a sense of connection — which is what the internet facilitates in parasocial dynamics. However, what is happening here isn’t parasocial, it’s mistaking art as a consumer-centric product.

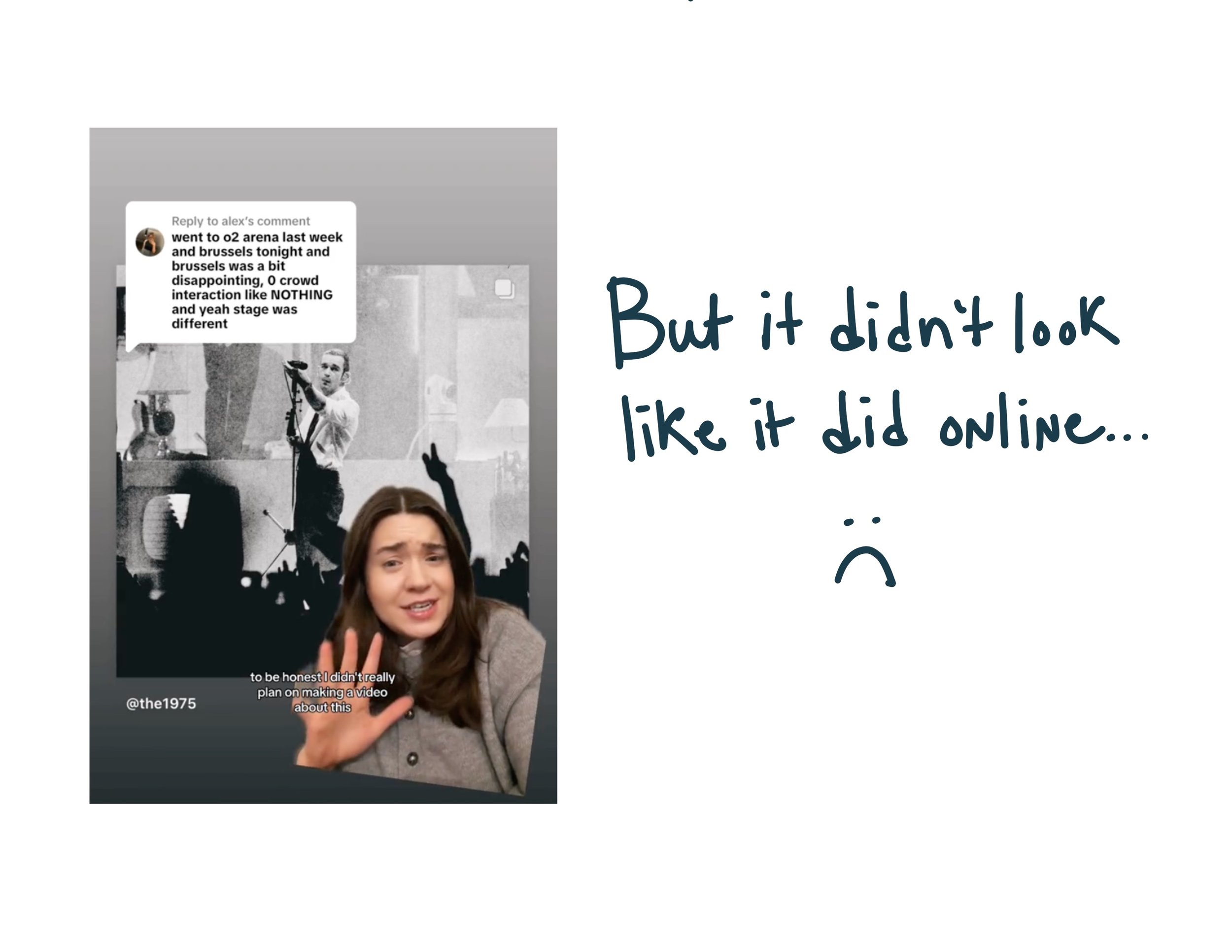

Berlin-based TikToker Britt-Marie (@itsthebml) is a resident commentator in the 1975 fan community on TikTok, and she replies to this comment on one of her videos with this, “To be honest I didn’t really plan on making a video about this, but it’s really starting to piss me off so badly.”

She goes on to talk about how frequently she receives comments from other fans complaining about changes in the show, the stage setup, and whether or not the band (notably Healy) is interacting with the fans enough.

And the observations are true — each show is different for a myriad of reasons. It could be language barriers, venue logistics, the temperament of the band that night, or just the fact that talking less means they can play more songs.

“I think that’s really something we all produce in our heads because we saw so much POV online,” says Britt-Marie. I reached out to her to talk more about this recurring complaint from fans who attended a live show.

People go to concerts for the music, this has remained true, especially before the pandemic. Since the return of live shows, with the 1975’s tour to be the first one to go viral post-pandemic, it’s become the latest measure of social currency and sense of superiority.

“And partially, we, as fans and fan culture have produced a setting where that is not enough anymore,” Britt-Marie continues. “And some artists have also fueled that, for example, Taylor [Swift] with the surprise songs or the 1975 with changing the setlist, which is by the way, something that’s that has always been fairly common for rock bands, right? It’s nothing new. But people are handling it like it’s a completely new occurrence, which is not the case.”

The TikTok-painted picture of these concerts is from the barricade warriors who “are always near the front row and upload little snippets of interactions, which could just be a look in a certain direction, or a movement of a hand gesture, whatever. People think that this stuff happens 24/7 at a show. And it just doesn’t but that’s because those videos are favored by the algorithm…because if you’re a 75 fan, it caters those videos to you.”

A montage of a personalized experience straight from your phone screen. It’s all on-demand, right? You saw the proof on the screen in your hand, so you can go do the same thing and see for yourself because you can have everything you want that you see online.

It couldn’t possibly be a fabricated, manipulated reality you’re imagining and find yourself outraged or disappointed when it doesn’t meet your expectations.

“People want to have their moment at a concert. If they don’t get it, it isn’t worth it,” Britt-Marie concludes.

Live Performance and Its Function

Fans of the 1975 are not all chronically-online, parasocial girlies — much of the fanbase intellectualizes the lyrics, imagery, and messages in the band’s media. There is a depth to their music that fans like Britt-Marie analyze on their TikToks and took notice of the significance of the theatrical segments of the At Their Very Best and Still…At Their Very Best shows.

These performances by Healy take place in the house lacking a fourth wall centered around toxic masculinity, the failings of the internet and the media, and his struggles as an artist.

Notably, the house includes multiple television sets — screens — broadcasting various scenes of the news and media.

Healy crawls through one of these television screens, disappearing from sight as he falls down the rabbit hole of indoctrination.

Clips from this theatrical segment made their rounds on TikTok as spectacle, a simulation of a reality that is inherently untrue — you are not the main character, the center of the universe, at the 1975 show.

We’ve lost the plot on what is reality, what is imagination, what is simulation, and what the differences between them are.

[S]imulating is not pretending: Whoever fakes an illness can simply stay in bed and make everyone believe he is ill. Whoever simulates an illness produces in himself some of the symptoms. Therefore, pretending… leaves the principle of reality intact: the difference is always clear, it is simply masked, whereas simulation threatens the difference between the “true” and the “false,” the real, and the imaginary.

Britt-Marie analyzes Matty Healy quoting Simulacra and Simulation on his Instagram story. (Watch the full video here.)

The context of a live performance’s purpose as a piece of art is lost in the flattened-out experience of social media. The actual performances only work functionally live in person.

It’s like when you read Shakespeare instead of witnessing a stage performance.

The literary text can be examined and critiqued. Still, each theatrical performance brings new meaning and attention, and each audience it is performed in front of changes the course of the performance.

A theatrical performance differs from a cinematic performance. It differs from an earnest, private interaction. It invites something else entirely — to participate in the performance and to bear witness as the audience — a role we don’t often get to play these days.

And as the audience, we have an active role in the performance at hand, just as much as the performers on stage.

“This two-way street between the actors and the audience suggests a co-dependent relationship. One cannot thrive without the enlistment of the other. And as much as the audience came to see the actors, the actors also came to see the audience…When a show manages to electrify the space, it is felt by everyone because a performance is not an individualistic experience. The audience is always plural, an emergent property of all the people who see the [performance]…To invite the audience to assimilate into the world we constructed, we created a portal between ordinary reality and transcendent reality. Usually, this portal is the door into the theater house: the division between outside and inside.” —An invitation to reconsider: The role of the audience, Yonatan Laderman, The Stanford Daily

The 1975’s Box was not a central feature of the set design for the touring show. For both ATVB and SATVB, the stage design was a house with lamps, windows, a drink cart, couches, and a rooftop all illuminated by a streetlight.

This was a theatrical performance — a stage play.

And the Box is still present as a doorway — a threshold crossed as the band takes the stage.

photo credit: The 1975 Official Account

The Box is now a portal between spaces — the bridge between our presumed true reality and the pocket universe in which the show takes place. It’s a lifeline out of the simulation or a test that many fans have failed.

The theatrical live performance of the 1975’s tour has been asking — pleading — for us as the audience to shed the simulation and to be an active audience, a united entity that comes together under the right conditions.

Validating the Moment

There are a few different ongoing bits of Healy-o Centric philosophy in The 1975 fandom. A couple of recent examples are: ”Does ‘baby girl’ mean camp?” or variations of “Don’t like menthols” in autotune.

Hilarious inside-jokes aside, Healy has asked the audience to question ourselves and why we do what we do, confronting this idea of validating the moment, this seeming need to document, archive, prove we did or saw something. Pics or it didn’t happen

“…it’s hard now to convince ourselves that anything has meaning. Cause look, I’m not judging you, but all of you truly believe that you can’t have this experience without validating it. You have to validate it by filming it. Because it has to have meaning. Cause where’s the meaning? I don’t know what fucking anything means anymore.” — Matty Healy, Singapore, July 19, 2023 (Courtesy of 1975archives)

For an indeterminate stretch of time, I have written my journal entries with the month, day, year, day of the week, and time. If I am writing somewhere other than my home, I will often include the name of the coffee shop or city I’ve traveled to.

I document the oddly specific detail telling me nothing other than when and where I scribbled out a lament or affirmation.

Documentation serves a purpose — a strange comfort in the face of oblivion, evidence of a time, a place, a sliver of a life, and opportunity for proof or story or both.

I think I add these measurements to my journal entries as an attempt at context. There is a valid argument for context facilitating meaning. Context, evidence, documentation can validate meaning and moments as…real, I suppose.

To validate is also to prove.

What if our drive to validate the moment is to validate identity markers? The identity of a fan, but not just any fan, a real fan.

If proof is required for something to be real, where is the proof for how my heart pounded in my chest as each song tempered on?

If proof is required for something to have been real, who am I wanting to prove something to?

Is my selfie in front of the stage proof for the band that I’m a real fan because I stood in the pit all night?

Or is it proof to broadcast to other fans I am more dedicated than those who haven’t attended a show because I flew across the country to see the band perform?

But maybe, mostly, terrifyingly so, I need proof for fear of life’s experiences and meaning slipping through my fingers like slick oil — leaving traces but never settling into stillness.

Our fear of missing out and the need to validate every moment of significance has given way to our participation in the Simulation — the constructed reality of the world we see through the screens in front of our eyes.

This is not an alarmist take on technology or a bid at fearmongering you into submission that all technology — smart devices, the internet, memes, algorithms, AI — is a festering evil we must renounce.

What this is — the contents of this essay, the information given to you through these words of pixelated light — is an examination of a reflection. The mirror before us is made opaque by our opiated point of view.

Injecting a live concert performance with a theatrical element is a calculated choice as it calls for a different role for the people in the crowd before the stage. A theatrical performance is a symbiotic dance between the performers and the audience.

When we only experience reality solely through a simulation screen, we are not participating, we are not an audience, we are a product and a perpetuator of the simulation.

To be the audience is to participate with and contribute to the live performance. It is a fleeting thing, an experience that cannot be faithfully duplicated. An artistic performance — theatrical or otherwise — is first and foremost intended to be lived presently.

The air, the atmosphere, the energy a crowd — the audience — brings into the pocket universe of the performance is unique.

The 1975 has been asking us for years to live in the moment, just for a moment, and share in the fleeting, fickle, earnest experience of the present.

On the contrary, Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour, while still a live performance and a testament to Swift’s monumental presence with incredible feats of production, planning, and logistics the show requires by design, is a product.

Which is not more or less than, morally inferior or superior, but it is different.

We’ve long viewed everything through consumption-colored lenses, our expectations of performance are warped and narrowed into a thin line of demand and entitlement.

I like that one thing you do, so do it all the time, and if I validate my identity with experiencing you live in-person, you better do that one thing. Because if you don’t, you’re fucking dead to me. You’re a product, don’t be defective or different. K love you bye.

Everything is Public, A Spectacle

Healy: “What’s your argument?”

Zahedi: “My argument is, no one knows what anything leads to. This is just the truth.”

Healy: “But it’s pub-but it’s public and like — ”

Zahedi: “Yeah but like, everything’s public now.”

Healy is caught on the implication of how complicated or “a lot” it is to impose publicity on children.

I don’t believe I heard of Caveh Zahedi until Healy referenced their interaction in episode 2 of A Theatrical Performance of an Intimate Moment, a series of short films uploaded on the 1975’s YouTube Channel.

The “full” meeting posted on Zahedi’s YouTube Channel, is referred to as a film. I would better describe it as a documentation of a conversation. Not quite a podcast, not really an interview, but definitely accurate by name — “Getting Stoned with Matty Healy.”

Of course, I googled him. Caveh Zahedi, I mean. It is a bit redundant, personally, for me to google Matty Healy. I came across a 2019 New York Times profile on Zahedi describing his brand of “audacity is so overwhelming as to be blinding.”

There is one particular moment between Healy and Zahedi that I find to be not only the most interesting in terms of conversation, but the thesis of the two coming together. It is this exchange where I believe Matty got what he came for: insight into his own artistic mind.

A sweeping response to the initial clips of ATVB and Healy’s various media appearances during the first few months of the tour was confusion, debate, and disgust. However, Healy has always been an honest artist, earnest in his rumination on the evolution of his body of work.

The short film series ATPOAIM laid Healy’s intent clear on the virtual page, and internet pedestrians seem to have missed this manifesto entirely.

Healy wanted to compare his artistic audacity to Zahedi’s, to measure what he is willing and wanting do against one of the furthest reaches of the spectrum.

Without something or someone to compare yourself to, can you see yourself clearly?

What is an artist to do when he questions his work and world? Remember, artists have artists too.What is an artist to do when he questions his work and world? Remember, artists have artists too.

Plainly and unbothered, Zahedi’s argument that everything is available for public consumption, observation, or judgment is justification for documenting everything. The act of documentation which is made available for mass consumption changes the context, however, even the context of the “truth” being documented.

I’ll never exhaust Marshall McLuhan from my analysis, at least, until I find another vehicle to drive my point in the direction of home. McLuhan told us the medium is the message, and it is unavoidable that media is transformed by the way it is transmitted and then again once received.

Healy noticed it with the initial performances of At Their Very Best…as bits and clips were shared on TikTok and Twitter, devoid of the intended context.

Is it inevitably unavoidable for an artist to exclude the potential context of the internet in art now?

And yet, it is the very nature of art being observed by an audience for the message or the text of the art to shift in context.

For my truth I see within yours may be miles apart from each other.

To Zahedi’s point in the fascinating exchange with Healy, we don’t know the effects of any of this — this being the mass accessibility to interpersonal effects morphed into media.

There could be positive outcomes and opportunities, but it’s idiotic or pure hubris to believe there won’t be negative consequences.

My Point, If Any

Media is here. Our lives are accessible to varying degrees to the public forum online, and many, many of us are living an extension of our everyday, interior lives the digital landscape.

We valid moments with a post on Instagram like a scrapbook or scoreboard. Which, by the way, there is nothing wrong with posting something on Instagram. It is okay to want to do that and like it.

Our lives are, to some extent, media. What we aren’t remotely prepared for is actively living with it.

Are we having conversations with each other, with our youth about the side effects, the consequences, the good AND the bad? Protest in your favor all you want, but you don’t even understand the full gravity of the situation. I barely do.

But I do know, and hope others will get on board with, is the internet is not some silly thing. Media is not some outside force; it is not other from us. And as we continue to deny it, we will remain trapped in a simulated reality.

What we do, say, create, and make cannot be exclusive from the internet or media.

I don’t think we’re doomed to a dystopian society or anything that dramatic. But I think we live in a level of denial about the whole thing.

Media literacy is evolving, we need more discernment and conversation.

If we are to live with media, we must recognize it. Even more so, we must know its imposter more intimately.

Performance, pretending, is not false or fake. It is art. It is imagination. It is what we visit with to be transformed and bring that transformation back with us into the world. From there we create our own moments of art.

But to pretend to not be pretending, to deny the tether to reality, that is false. That is fake. That is a simulation.

Recently, I’ve been listening to the audiobook of Rick Rubin’s The Creative Act: A Way of Being, and this line struck me like lightning:

“Impatience is an argument with reality.”

We are impatient, it is human. Yet as our lives have become intertwined with media, becoming media ourselves, our natural impatience has mutated into something else — at times monstrous.

It is natural for us to want to capture what is fleeting, but it cannot be contained. Instead, we document, and today, we replicate these moments as uncanny facsimiles.

We do it with things we love, including the artists we go to experience in person. But again, we’ve lost the plot. As if replicating, and then validating what they saw online as our own experience, is the most important thing in the world.

It won’t make it better, it won’t feel like a fond memory to look back on with wrinkled eyes.

We get frustrated, angry, hateful, and demanding of artists like Matty Healy because they challenge our perception of reality, and they don’t operate as content machines.

“We’re not living life in reality anymore. 2020 smashed our existences into our phones and into the digital world, and we are no longer existing in our physical space…We are living in a digital world that isn’t even real. It’s basically a video game.” — Mike Mancusi, TikTok

I came across comedian Mike Mancusi’s video talking about life not feeling like real life anymore as I scrolled on my phone. Very apropos.

None of this is a coincidence.

We haven’t been living in reality.

While I don’t believe the answer lies in renouncing our smartphones and cleansing our homes from WiFi, waving palo santo around from room to room, I do believe we need to take this seriously.

How can I, as a writer, in today’s world, communicate any of this to you without the internet? As kitschy and nostalgic as it may be to start a print zine out of my home office and snail mail my essays to you, that’s not necessarily practical.

Also, I don’t have your address. And frankly, I’m not signing up for Stamps.com anytime soon.

We don’t need to blame artists for not performing how we want them to perform or rage tweet when they don’t meet our expectations. They are trying to tell us something.

Art is the answer, the rebellion, the revolution, the thing we have been missing. Not the POV.

You don’t need to touch grass. You need to see art and let it change you, let it affect you in fleeting moments. Then go make art.

And thank Matty Healy while you’re at it.